Smaller Contour Intervals: 7 Hidden Disadvantages Revealed!

Ever looked at a highly detailed topographical map and thought, “the smaller the contour interval, the better the map must be”? It’s a common assumption, rooted in the belief that more detail always equates to superior precision and Terrain Representation. But what if this intuitive notion holds a hidden paradox? What if the pursuit of hyper-fine Contour Intervals introduces significant, often overlooked disadvantages that can severely impact Map Readability, escalate Survey Costs, and even lead to Terrain Misinterpretation?

In this deep dive, we’re not just challenging a widespread belief; we’re unveiling the critical reasons why, in the complex world of Cartography, opting for Smaller Contour Intervals isn’t always better. Prepare to discover the unseen chaos, the draining resources, and the digital burdens that often come with too much detail, ultimately compromising the overall Cost-Effectiveness and utility of your Topographical Maps.

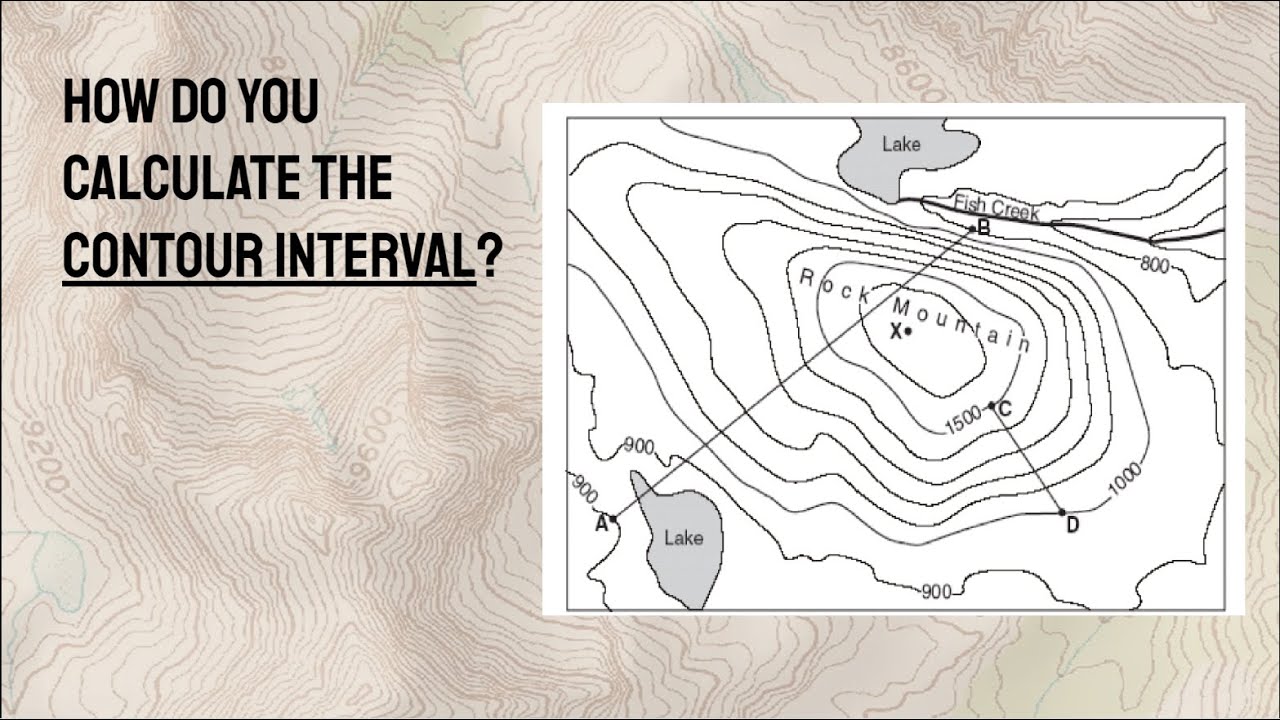

Image taken from the YouTube channel Diane Gunnip , from the video titled Calculating Contour Intervals .

When visualizing the Earth’s varied surface on a flat map, few elements are as crucial as contour lines, serving as the silent narrators of elevation and terrain.

The Allure of Detail: Why Smaller Contours Aren’t Always the Smarter Choice

At the heart of every topographical map are contour lines, imaginary lines that connect points of equal elevation above a reference datum, typically sea level. These lines provide a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional landscape, allowing map users to visualize hills, valleys, slopes, and peaks. The contour interval is the fixed vertical distance between any two successive contour lines. For example, a map with a 10-meter contour interval means that each contour line represents an elevation difference of 10 meters from its adjacent lines. This fundamental parameter is crucial for conveying the steepness and shape of terrain features.

It’s a common, intuitive assumption among map users and even some cartographers that when it comes to terrain representation, smaller contour intervals equate to superior precision and a more detailed understanding of the landscape. The logic seems straightforward: more lines mean more information, and more information means greater accuracy. This belief often leads to the conclusion that a map with, say, a 1-meter interval is inherently ‘better’ than one with a 10-meter interval, offering a far more granular and therefore more useful depiction of the ground.

However, this seemingly logical progression from smaller intervals to greater utility doesn’t always hold true in practice. While the appeal of granular detail is undeniably strong, opting for smaller contour intervals can introduce significant, often overlooked disadvantages that compromise rather than enhance a map’s effectiveness. What initially appears as a straightforward improvement can, in fact, complicate the very purpose of a topographical map.

This section will delve into this often-unseen paradox. We will explore how choosing excessively smaller contour intervals can inadvertently trigger a cascade of ‘hidden disadvantages’ that profoundly impact map readability, inflate survey costs, and ultimately diminish the overall cost-effectiveness in cartography. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for creating truly functional and efficient topographical maps that serve their intended purpose without overwhelming the user or the budget.

The first and perhaps most evident challenge posed by an overabundance of contour lines is the sheer visual confusion they can create.

Continuing our discussion on why smaller contour intervals aren’t always superior, let’s first delve into the most immediate visual impact of this approach.

Lost in the Lines: The Visual Cacophony of Overly Detailed Topographical Maps

When it comes to topographical maps, the intuitive belief is often that more detail equates to greater accuracy and utility. However, this pursuit of hyper-precision, particularly through the use of smaller contour intervals, can ironically lead to a significant degradation in the map’s overall effectiveness. Instead of enhancing understanding, it can transform a valuable navigational tool into a visually overwhelming and frustrating experience.

The Dense Web of Lines: From Detail to Indistinguishability

One of the most immediate and profound consequences of employing smaller contour intervals is the sheer proliferation of contour lines on the map. In areas characterized by steep inclines, rugged topography, or highly complex terrain, these closely spaced lines quickly converge. This abundance creates dense, indistinguishable areas where individual contour lines lose their definition and merge into an opaque, solid mass of ink. What was intended to be a precise representation of elevation turns into an unreadable tangle, making it nearly impossible to discern specific elevation changes or the subtle nuances of the landscape. Imagine trying to read a finely printed document where all the letters are smudged together – that’s the effect excessive contour lines can have on a map.

Obscuring the Essentials: The Readability Crisis

This phenomenon, commonly known as "map clutter," has a direct and severe impact on overall map readability. Topographical maps are not solely about elevation; they are complex repositories of critical geographic information. Roads, rivers, trails, buildings, land-use boundaries, and other man-made structures are just as vital for navigation, planning, and analysis. When the map is overwhelmed by a dense network of contour lines, these crucial elements become obscured, difficult to locate, or even completely invisible. A major highway might appear as a faint line through a thicket of contours, or a small but important village could be swallowed by the topographical noise. This forces users to strain their eyes and dedicate excessive time to deciphering even the most basic features, significantly hampering the map’s core function.

The Cost of Visual Overload: Frustration and Misinterpretation

The visual overload inherent in maps with excessive contour detail directly hinders quick interpretation, a critical factor in many applications. For instance:

- Emergency Response: First responders, often operating under severe time constraints, need to quickly identify the easiest routes, potential obstacles, and safe zones. A cluttered map slows down decision-making, potentially endangering lives.

- Military Operations: Rapid assessment of terrain for tactical advantages or movement planning is paramount. Visual noise can lead to misjudgments of slope, cover, or line of sight, with potentially grave consequences.

- Outdoor Recreation: Hikers or mountaineers rely on maps for route finding and understanding the terrain ahead. A map that induces confusion rather than clarity can lead to frustration, errors in navigation, and even safety risks.

This constant struggle to extract information from a visually dense map inevitably leads to user frustration. What should be an intuitive tool becomes an impediment, eroding confidence and increasing the likelihood of errors.

When More Is Less: Counterproductive Detail

There are numerous scenarios where excessive detail from smaller contour intervals becomes counterproductive, making the map less functional for its intended purpose:

- Broad Regional Planning: For urban planners or ecologists assessing large areas, fine-grained elevation details are often irrelevant and simply add noise, distracting from macro-level patterns like watershed boundaries or broad elevation zones.

- Rapid Route Planning: When a quick overview of a region’s general topography is needed (e.g., planning a cross-country drive), a map saturated with every minor undulation of the land is inefficient and makes it harder to identify major valleys or mountain ranges.

- Navigating in Dense Environments: In areas with significant tree cover or urban sprawl, the added clutter from very small contour intervals often compounds existing visibility issues, making it harder to triangulate positions or identify landmarks.

In essence, while precision is valuable, there’s a point of diminishing returns where additional detail ceases to be informative and instead becomes detrimental, transforming a map from a guide into a puzzle.

Beyond the immediate visual and practical challenges posed by map clutter, the pursuit of such granular detail also introduces significant logistical and financial burdens, which we will explore next.

While excessive detail can indeed obscure a map’s clarity, the pursuit of incredibly fine contour intervals often comes with another, more tangible consequence: a significant drain on financial resources.

The Price of Precision: Why More Detail Costs More Than You Think

Achieving a high level of detail in terrain representation, particularly through smaller contour intervals, is far from a free endeavor. It directly translates into a substantial escalation in survey costs, impacting project budgets and often challenging the very cost-effectiveness of mapping initiatives. This increase stems from a fundamental need for more data, more time, and more sophisticated tools and expertise.

The Direct Correlation: More Detail, More Data, More Expense

The relationship between a smaller contour interval and higher survey costs is remarkably direct and often exponential. Every contour line on a map represents a specific elevation. When the interval between these lines is reduced (e.g., from 5 meters to 1 meter), the number of contour lines that need to be derived for a given area increases dramatically. Each of these lines requires a denser network of accurate elevation points from the ground. Collecting this exponentially larger volume of precise data points is the primary driver of increased expenditure. It’s not just a linear increase; acquiring twice the detail often requires far more than twice the effort and resources.

Time, Labor, and the Pursuit of Density

The process of land surveying for fine-interval contour lines is inherently time-consuming and labor-intensive. To gather the denser network of points required:

- Extended Fieldwork: Survey crews must spend significantly more time on site, meticulously collecting elevation data. This means more days, weeks, or even months dedicated solely to fieldwork, leading to higher labor costs and logistical expenses (travel, accommodation, per diems).

- Increased Data Acquisition: Instead of capturing points every few meters, surveyors might need to record data at sub-meter intervals, especially in areas with subtle terrain changes. This painstaking process slows down progress considerably.

- Extensive Post-Processing: Once the vast amount of raw data is collected, it requires extensive processing, cleaning, and quality control in the office. This involves more hours for skilled technicians and engineers, further inflating labor costs.

Investment in Advanced Equipment and Specialized Expertise

Achieving sub-meter or even sub-foot elevation accuracy demands more than just dedicated time; it necessitates investment in cutting-edge technology and highly skilled personnel:

- Precise Survey Equipment: Basic GPS units or standard total stations may not offer the precision required for very small contour intervals. Surveyors must instead utilize advanced equipment such as RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) GPS systems, high-resolution terrestrial laser scanners (LiDAR), or sophisticated drone-based photogrammetry and LiDAR platforms. These technologies are significantly more expensive to acquire, calibrate, maintain, and insure.

- Specialized Software: Processing the massive datasets generated by advanced equipment (e.g., point clouds from LiDAR) requires specialized, high-performance software, which often comes with substantial licensing fees.

- Highly Skilled Professionals: Operating and interpreting data from these advanced tools requires specialized expertise. Surveyors capable of managing such complex projects and ensuring the accuracy of detailed terrain models command higher salaries, adding to the overall project cost.

Budgetary Impact and Cost-Effectiveness Compromise

The cumulative effect of increased labor, sophisticated equipment, and specialized expertise can severely impact project budgets:

- Budget Overruns: Projects initially estimated with standard contour intervals can quickly face significant budget overruns if finer detail is later deemed necessary, leading to financial strain.

- Compromised Project Scope: Escalating mapping costs might force project managers to reduce the scope of other critical project components or delay timelines, impacting overall efficiency.

- Economic Non-Viability: For large-scale mapping projects, the costs associated with achieving extremely small contour intervals can become prohibitive, rendering the endeavor economically non-viable. The added value of minute detail often does not justify the disproportionate increase in expenditure.

To illustrate, consider the approximate relative increase in survey costs as contour intervals decrease:

| Contour Interval (Meters) | Approximate Relative Survey Cost |

|---|---|

| 5 | 1x (Baseline) |

| 2 | 1.5x – 2x |

| 1 | 3x – 5x |

| 0.5 | 6x – 10x |

| 0.25 | 12x – 20x |

Note: These are illustrative ranges and actual costs can vary significantly based on terrain, access, location, and specific project requirements.

This table highlights that demanding twice the "detail" in contours can easily lead to a quadrupling or more of the surveying expenses, demonstrating a clear trade-off between the perceived precision and the financial outlay.

However, even when resources are poured into acquiring such granular data, a curious paradox emerges: the illusion of detail might not always translate into clearer understanding.

Even after grappling with the escalating financial and logistical burdens of generating highly detailed contour data, a more subtle, yet equally profound, challenge emerges: the potential for such rich detail to become a hindrance rather than a help.

The Clarity Conundrum: How More Contour Lines Can Cloud Your View of the Land

Paradoxically, an overwhelming abundance of information, particularly from maps with very small contour intervals, can obscure rather than illuminate the true nature of the landscape. While intuitively one might assume more detail always leads to better understanding, in the realm of terrain mapping, it can often lead to an "illusion of detail"—a deceptive sense of precision that makes it harder for users to quickly grasp the major terrain features and overall topography.

Drowning in Data: When Nuance Becomes Noise

Maps with extremely small contour intervals, like 0.5 or 1 meter, are designed to capture every subtle shift in elevation. However, this level of granularity can have unintended consequences:

- Over-Emphasis of Minor Undulations: Every small rise, dip, or subtle change in slope, which might be insignificant in the grand scheme of the landscape, becomes prominently depicted. These minor undulations can clutter the map, drawing the eye to inconsequential features.

- Distraction from Primary Features: As a result of this emphasis on minor details, the primary slope, the general form of the land, and the significant macro-features (like large valleys, prominent ridges, or broad plateaus) can become visually lost amidst a dense web of closely packed contour lines. It’s akin to trying to discern the shape of a forest by focusing on the individual leaves of every tree. The overall pattern, flow, and structural integrity become difficult to discern at a glance.

The Peril of Misinterpretation: Skewed Decisions

This "illusion of detail" carries significant risks, particularly when critical decisions hinge on an accurate understanding of the terrain. When users base their analysis on an ungeneralized, overly detailed view, they are prone to terrain misinterpretation, leading to potentially costly or dangerous errors:

- Water Flow Analysis: A map cluttered with minor contours might make it challenging to accurately predict primary water flow paths. Small depressions or minor rises could be mistaken for significant drainage divides, leading to incorrect assessments for storm water management or irrigation systems.

- Optimal Building Sites: Identifying ideal locations for construction requires understanding the overall stability and slope of the land. Over-emphasis on minor variations could lead to misjudging a site’s suitability, potentially placing structures in areas prone to erosion or unstable ground, or overlooking more stable, gently sloped areas.

- Safe Route Planning: For navigation, road construction, or emergency response, understanding the macro-topography is paramount. A map that makes it hard to distinguish between a gentle, consistent slope and a series of minor, undulating rises and falls could lead to miscalculations regarding accessibility, travel time, or the feasibility of a route. Decisions are then based on an inaccurate mental model of the terrain, derived from an excess of raw, unfiltered data.

The Power of Perspective: Clarity Through Simplification

Ironically, sometimes less is truly more. Simplification, achieved through the use of larger contour intervals, can often provide a clearer and more actionable understanding of the landscape’s macro features.

- Highlighting Macro Features: Larger intervals (e.g., 5-meter or 10-meter) effectively filter out the "noise" of minor undulations, allowing the dominant slopes, major ridges, valleys, and overall landforms to stand out. This presents a more generalized, yet often more functionally accurate, representation of the terrain.

- Enhanced Legibility: Maps with fewer, more widely spaced contour lines are inherently easier to read and interpret quickly. This improved legibility reduces cognitive load, enabling users to rapidly grasp the essential characteristics of the land.

- Actionable Insights: For many planning and decision-making purposes, understanding the broad strokes of the landscape is far more critical than knowing every centimeter of elevation change. A simplified map can provide the necessary context and actionable insights without overwhelming the user.

Therefore, the pursuit of ultimate precision in contour mapping can, counter-intuitively, lead to a loss of clarity and an increased risk of misinterpretation. This challenge, where raw data overwhelms clear understanding, extends beyond human cognition, presenting significant processing and storage demands for the systems designed to manage such vast quantities of geographical information.

Beyond the perceptual challenges of misinterpreting terrain features at overly fine detail, the pursuit of ever-smaller contour intervals introduces a new set of significant technical hurdles within the digital realm.

When Precision Becomes a Problem: The Computational Cost of Over-Detailed Terrain Data

In the age of digital mapping, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are the backbone of terrain representation. While the impulse might be to capture every minute detail, doing so by adopting smaller contour intervals comes with a substantial digital burden, affecting everything from storage to user experience.

The Exploding Dataset: Storage and Management Challenges

The most immediate consequence of using smaller contour intervals is the exponential growth in data volume. Each additional contour line, generated to represent a finer elevation change, adds more geometric data points and attributes to the dataset.

- Vast Storage Requirements: These high-resolution terrain models can quickly consume vast amounts of disk space, necessitating more expensive storage solutions and complex archiving strategies.

- Data Management Complexity: Handling, indexing, and organizing terabytes of elevation data becomes a significantly more intricate task, increasing the potential for errors and requiring specialized database management systems.

- Sharing and Distribution Bottlenecks: Transferring these massive files, whether across networks, between departments, or to external collaborators, becomes slow and resource-intensive, often requiring specialized tools or highly compressed formats that can degrade data quality.

The Performance Drag: Processing Power and Time

Once stored, these large datasets demand considerable computational resources for any form of interaction or analysis within GIS software.

- Rendering Strain: Displaying intricate terrain models with hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of contour lines requires powerful graphics processing units (GPUs) and significant RAM. The software must calculate and render the position of each line, which can lead to slow map loading times and sluggish panning or zooming, frustrating users and hindering workflow efficiency.

- Analysis Overheads: Any analytical operation, such as calculating slope, aspect, or performing visibility analyses, becomes computationally intensive. Algorithms designed to process terrain data must iterate through vastly more data points, leading to significantly longer processing times. This can turn quick queries into hours-long computations, impacting project timelines and analytical agility.

- Increased Computational Costs: The need for more powerful hardware (faster processors, larger memory, dedicated graphics cards) directly translates to higher capital expenditure. Furthermore, the increased processing time means more energy consumption and potentially higher operational costs, especially in cloud-based GIS environments where computing time is often billed.

Web and Mobile Constraints: Impact on Map Readability

The challenges extend beyond desktop GIS environments, profoundly affecting the usability of maps on web-based platforms and mobile devices, where resources are inherently limited.

- Bandwidth Limitations: Serving high-resolution contour data over the internet or cellular networks demands significant bandwidth. Users with slower connections will experience painfully long loading times, or the map may fail to load entirely.

- Device Processing Capabilities: Mobile phones and tablets, despite their advancements, have far less processing power and memory than desktop workstations. Attempting to render or interact with overly detailed terrain data on these devices often leads to poor performance, crashes, or a completely unresponsive application.

- Compromised Map Readability: Ironically, on smaller screens or with limited processing power, excessive detail can actually reduce map readability. Features become cluttered, lines merge, and the map transforms into an illegible tangle of information, defeating the purpose of high-resolution data. Users are left squinting at a complex image rather than gaining clear insights.

The drive for ever-finer detail, while seemingly beneficial, can paradoxically degrade the user experience and create an unnecessary technical burden that outweighs any perceived accuracy gains, especially when considering the ultimate viewing context. This brings us to a crucial consideration: how the level of detail aligns with the intended purpose and scale of the map.

While the digital age presents the challenge of overloading Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with excessively fine-grained data, an equally critical concern arises when this detailed information, particularly in cartography, fails to translate effectively to its intended display.

Navigating the Paradox of Precision: When Smaller Contours Lose Their Way

In the intricate world of cartography, the accuracy and utility of a map are not solely determined by the raw volume of data it contains. A fundamental principle dictates that the level of detail presented must be appropriate for the map’s intended scale and purpose. This becomes particularly evident when examining the critical relationship between Contour Intervals and Map Scale.

The Symbiotic Link: Contour Intervals and Map Scale

Contour Intervals represent the vertical distance or difference in elevation between adjacent contour lines on a topographic map. A smaller contour interval signifies a map with greater detail in elevation changes, ideal for showing subtle terrain features. Conversely, Map Scale defines the ratio between a distance on the map and the corresponding distance on the ground. A "large scale" map (e.g., 1:5,000) shows a small area with significant detail, while a "small scale" map (e.g., 1:1,000,000) depicts a large geographic area with less detail.

The relationship between these two elements is symbiotic. For a map to be both accurate and readable, the chosen contour interval must be in harmony with the map’s scale.

The Diminishing Returns of Fine Detail

The inherent benefits of capturing fine detail through Smaller Contour Intervals (e.g., 1-meter intervals) diminish significantly or become entirely lost when the map is printed or viewed at a smaller Map Scale (e.g., 1:250,000). At such scales, individual contour lines from a fine interval become so closely packed that they merge into an indecipherable blur, obscuring rather than revealing topographic information. What was intended as precision transforms into visual noise, severely compromising Map Readability and clarity. The fine nuances of terrain that small intervals are designed to show simply cannot be perceived at a broad regional or national overview.

The Imperative of Generalization in Mapping

This redundancy of detail directly leads to the critical cartographic concept of generalization. Generalization is the process of simplifying the representation of geographic features on a map to maintain clarity and legibility at a given scale. It necessitates the removal or simplification of excessive detail that would otherwise clutter the map. When mapping at smaller scales, features that are distinct at larger scales (like individual small ridges or depressions shown by fine contours) become too small to be represented individually. Therefore, fine intervals become ineffective for broader views, as the map designer must generalize these features anyway, rendering the initial high-resolution contour data superfluous. The goal shifts from showing every ripple in the landscape to presenting the overall shape and major elevation trends.

Scaling Up: Appropriate Intervals for Broader Views

Consequently, at regional or national Map Scales, Larger Contour Intervals are often more appropriate. For instance, a map of an entire state might use 50-meter or 100-meter contour intervals, while a local hiking trail map might use 5-meter or 10-meter intervals. These larger intervals prevent clutter, maintain Map Readability, and clearly convey the general topographic character of vast areas without unnecessary precision that cannot be discerned. Choosing the correct interval is not about sacrificing accuracy but about optimizing the presentation of information for the specific viewing scale and purpose.

The table below illustrates common recommendations for appropriate contour interval ranges based on typical map scales:

| Map Scale (Ratio) | Typical Geographic Coverage | Recommended Contour Interval Range (meters) | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:5,000 – 1:10,000 | Small Local Area (e.g., Park, Campus) | 1 – 5 | Site Planning, Detailed Engineering Surveys |

| 1:24,000 – 1:25,000 | Neighborhood, Local Community | 5 – 10 | Hiking, Urban Planning, Local Resource Management |

| 1:50,000 – 1:100,000 | Regional, Small County | 10 – 20 | Regional Planning, Broad Navigation, Geological Mapping |

| 1:250,000 | Large Regional, State Section | 20 – 50 | State Planning, Aviation Charts, Major Highway Maps |

| 1:500,000 – 1:1,000,000 | National, Large State, International | 50 – 200 | National Overview, Strategic Planning, Climate Studies |

Understanding this delicate balance ensures that maps are not just repositories of data, but effective communication tools, delivering relevant information without overwhelming the user. However, generating and maintaining this "just right" amount of detail also introduces its own set of practical challenges.

Beyond the immediate challenges of visual clutter and scale mismatch, the choice to include smaller contour intervals introduces a significantly greater hurdle: ongoing maintenance.

The Perpetual Refresh: Navigating the Maintenance Maze of Micro-Contour Maps

The allure of highly detailed topographical maps, featuring very smaller contour intervals, is undeniable, offering an intricate portrait of the terrain. However, this pursuit of hyper-precision comes with a significant and often underestimated cost: the formidable effort required to keep such maps current.

The Escalating Burden of Fine-Grain Detail

Maintaining topographical maps is an ongoing process, but the intensity of this effort scales dramatically with the chosen contour interval. Maps designed with very smaller contour intervals demand an exceptionally high level of maintenance, translating directly into increased effort and substantial survey costs. Every subtle undulation, every minor elevation change, is captured, and consequently, every subtle change on the ground necessitates a costly update.

The Ripple Effect of Minor Terrain Shifts

The sensitivity of maps with fine contour intervals means that even seemingly minor alterations in the landscape can render large sections of the map obsolete. Consider the following:

- New Construction: The erection of a single large building, a new road, or even a significant landscaping project can dramatically alter local elevation profiles.

- Erosion: Natural processes like wind or water erosion, particularly in dynamic environments, can subtly reshape hillsides and valleys over time.

- Significant Land Disturbance: Activities such as mining, large-scale agriculture, or major infrastructure development can cause substantial and rapid changes to the terrain.

For maps with smaller contour intervals, each of these changes requires extensive re-surveying of the affected areas. This isn’t just a quick check; it involves meticulous data collection, often using advanced technologies like LiDAR or high-precision GPS, followed by complex data processing to integrate the new information accurately into the existing map data. The sheer volume of data points required for fine-interval contours means that updates are laborious and time-consuming.

The Contrast: Larger Intervals, Lighter Load

In stark contrast, topographical maps utilizing larger contour intervals offer a significant advantage in terms of maintenance. Their inherent generalization means they capture the broader shape of the land rather than every minute detail. Consequently:

- Minor terrain changes often fall within the acceptable generalization of the map and do not necessitate immediate or extensive re-surveying.

- Updates are required less frequently and are generally less intensive, as the focus remains on significant, macro-level changes to the landscape.

- The data processing for updates is also less complex and less resource-intensive, as fewer detailed data points are being managed.

This difference in maintenance burden contributes significantly to the long-term viability and practicality of map products.

The Long-Term Equation: Accuracy, Longevity, and Cost

The persistent challenges of updating highly detailed map products have a profound impact on their longevity, accuracy, and overall cost-effectiveness over time. A map with smaller contour intervals might be highly accurate on the day it’s published, but its precision quickly degrades in dynamic environments if not continually updated. The financial and logistical demands of this perpetual update cycle can quickly outweigh the initial benefits of the granular detail. Organizations and users are faced with a dilemma: invest heavily in continuous updates, accept a diminishing level of accuracy, or frequently purchase entirely new map editions. This makes highly detailed maps a high-maintenance asset, significantly impacting their long-term value proposition.

These extensive maintenance demands inevitably lead us to question the overall value proposition, where the quest for extreme detail may, in fact, yield diminishing returns.

While the previous section highlighted the practical difficulties and high maintenance associated with mapping exceptionally fine terrain details, it’s also crucial to consider whether such extreme precision is always beneficial.

The Precision Trap: Navigating the Trade-Off Between Detail and Practicality in Mapping

In the pursuit of perfect accuracy, cartographers might inadvertently fall into a "precision trap," where the quest for infinitesimally smaller contour intervals yields diminishing returns. While the allure of hyper-detailed topographical maps is understandable, a critical analysis reveals that beyond a certain point, the marginal gain in accuracy becomes negligible for most practical applications, often outweighing its significant associated costs and potential drawbacks.

The Point of Diminishing Utility

The argument for ever-smaller contour intervals often assumes that more detail is always better. However, this is not universally true. For many common uses of topographical maps—such as general navigation, land-use planning, or understanding regional hydrology—a certain level of detail is sufficient. Improving on this with micro-level contours might only provide an incremental, almost imperceptible, increase in practical accuracy. Imagine needing to know if a hill is 100 meters or 100.1 meters high; for most purposes, this 0.1-meter difference is irrelevant and doesn’t change how the map is used.

The Steep Cost of Hyperscale Detail

The trade-off for this negligible gain in accuracy is substantial. Mapping with extremely small contour intervals significantly escalates:

- Survey Costs: Gathering the vast amount of precise elevation data required for very small intervals demands more extensive field surveys, high-resolution aerial photography, or advanced LiDAR scanning, all of which are expensive and time-consuming.

- Data Burden: Higher detail translates directly into larger datasets, which require more robust storage, processing power, and specialized software. This can complicate map production, distribution, and even simple viewing on common devices.

- Map Clutter: Paradoxically, more detail can make a map harder to read. An abundance of closely packed contour lines can obscure other vital map features like roads, buildings, or vegetation, turning a valuable tool into a dense, confusing graphic.

- Terrain Misinterpretation: In some cases, an overly dense representation of contours can lead to misinterpretation. Minor, localized undulations might appear as significant features, drawing attention away from the broader topographical patterns or critical terrain changes.

Consider the hypothetical relationship between accuracy and cost as contour intervals decrease:

| Contour Interval (m) | Relative Accuracy Gain (Cumulative) | Relative Cost Increase (Cumulative) | Practical Utility Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Low | Low | Basic understanding |

| 50 | Moderate | Moderate | General navigation |

| 20 | High | Significant | Detailed planning |

| 10 | Very High | Very Significant | Specific engineering |

| 5 | Marginal | Exponential | Niche, highly specialized |

| 1 | Negligible | Extreme | Rarely justifiable |

As this table illustrates, moving from 20-meter to 5-meter intervals provides less proportional accuracy gain compared to the cost increase. Beyond a certain point, the cost curve rises sharply while the accuracy curve flattens.

When Simplicity Suffices: Examples of Larger Interval Efficacy

There are numerous scenarios where larger contour intervals provide more than sufficient precision without incurring excessive overhead:

- Hiking and Backpacking Maps: For general outdoor recreation, 20-meter or 40-meter intervals are often ideal, providing enough information to understand terrain changes without overwhelming the user with unnecessary detail that might obscure trails or points of interest.

- Regional Planning and Environmental Assessments: At a broader scale, intervals of 50 meters or even 100 meters can accurately depict major watersheds, mountain ranges, and valley systems, facilitating large-scale decision-making without the burden of granular data.

- Educational Maps: Maps used in classrooms or for general public awareness benefit from clarity. Larger intervals present topographical concepts more clearly, making them accessible to a wider audience.

- Road Network Planning (Early Stages): For initial assessments of potential road routes over large areas, broader contour intervals help identify general gradients and major obstacles, leaving fine-tuning to later, more localized surveys.

A Balanced Approach to Terrain Representation

Ultimately, effective cartography is about striking a balance. It’s about prioritizing cost-effectiveness and practical utility over an often-unnecessary pursuit of ultimate detail in terrain representation. The goal is not to map every single undulation, but to provide the right amount of detail necessary for the map’s intended purpose and audience. Over-specifying contour intervals can lead to wasted resources and a less effective map, while an appropriate choice can deliver precision where it matters without the associated drawbacks.

Understanding these limits is the first step towards striking the optimal balance, a critical aspect we will explore next.

Having explored the pitfalls where the pursuit of excessive detail in topographical maps can lead to diminishing returns and inflated costs, the critical question then shifts from "how much detail can we add?" to "how much detail should we add?"

The Optimal Chord: Harmonizing Detail and Utility in Topographic Mapping

Achieving an effective topographical map is less about cramming in every minute detail and more about a strategic calibration of information. The previous discussion highlighted the point where additional detail no longer adds value, but instead introduces complications. This section focuses on identifying that ‘sweet spot’ – the optimal contour interval that delivers clarity, utility, and cost-effectiveness.

The Double-Edged Sword of Excessive Detail

While an initial instinct might suggest that more detail is always better, employing overly small contour intervals—meaning contours are very close together, depicting every minor change in elevation—carries several significant, often hidden, disadvantages. These pitfalls underscore why a ‘less is more’ approach can often yield a superior product.

The Seven Hidden Drawbacks of Overly Small Contour Intervals

- Visual Clutter and Reduced Readability: When contours are packed too densely, the map becomes visually overwhelming. The individual lines merge into a confusing mass, making it difficult for users to quickly discern major elevation changes, identify features, or follow specific contours. This ‘visual noise’ significantly impairs map readability.

- Inflated Data Collection Costs: Achieving very small contour intervals demands extremely precise and time-consuming field surveys or high-resolution remote sensing data. This translates directly into substantially higher costs for data acquisition, labor, and specialized equipment.

- Increased Production and Printing Costs: Handling and processing massive datasets generated by fine contour intervals require more powerful computing resources and longer processing times. For physical maps, the sheer density of lines can increase printing complexity, ink consumption, and overall production expenses.

- GIS Performance Bottlenecks: High-resolution contour data can place a significant strain on Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Loading, rendering, analyzing, and managing such large datasets can lead to slower performance, increased processing times, and potentially require more robust and expensive hardware infrastructure.

- Risk of Misleading Terrain Interpretation: An excessive focus on minute elevation changes can distract users from the broader, more significant topographic features. Users might misinterpret the overall slope or character of the terrain by fixating on minor undulations that hold little practical importance for their purpose.

- Limited Map Utility and Broader Appeal: Maps with extremely fine contour intervals often become highly specialized, catering to a very niche audience (e.g., highly precise engineering projects). This reduces their versatility and accessibility for general navigation, planning, or educational purposes, limiting their overall utility.

- Data Redundancy and Storage Inefficiency: A substantial portion of the highly granular data depicted by overly small contour intervals may offer negligible additional practical information for the map’s primary use. This leads to inefficient data storage, larger file sizes for sharing, and unnecessary data management complexities.

Calibrating for Clarity: The Strategic Imperative of Contour Interval Choice

The core message is clear: the optimal contour interval is not a universal standard but a strategic decision. It requires careful consideration of various factors to ensure the map effectively serves its intended purpose without unnecessary overheads or visual clutter.

Key Determinants of Optimal Contour Intervals

The ‘right’ interval fundamentally hinges on:

- The Map’s Primary Purpose: Is it for hiking, where general slope is key? For engineering, where precise gradients are critical? For urban planning, where building heights matter? Each purpose demands a different level of detail.

- The Target Audience: Will the map be used by experienced professionals, casual hikers, or students? The audience’s familiarity with topographic maps and their specific information needs should guide the level of detail.

- The Map Scale: This is a crucial relationship. A large-scale map (showing a small area in great detail, e.g., 1:1,000) can accommodate smaller contour intervals than a small-scale map (showing a large area with less detail, e.g., 1:250,000), where fine contours would simply merge into an unreadable blob.

- Budget Constraints: The available financial resources directly impact the feasibility of collecting and processing high-resolution data, thus influencing the practical choice of contour interval.

Critical Factors Beyond Precision

Beyond the core determinants, map creators must also actively weigh:

- Map Readability: The paramount goal is a map that is easy to understand and interpret. The chosen contour interval must prevent visual clutter and allow for clear representation of terrain features.

- Survey Costs: The financial implications of data collection for a specific contour interval must be thoroughly evaluated to ensure the project remains cost-effective.

- Terrain Misinterpretation Risks: The interval should be chosen to accurately convey the significant characteristics of the terrain, avoiding detail that could lead users to misjudge the overall landscape.

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Processing Capabilities: Practical considerations regarding the software and hardware resources available for data processing, analysis, and rendering are vital to ensure efficiency.

Towards Purposeful Topography: Balancing Precision with Practicality

In essence, effective topographical mapping is an exercise in thoughtful compromise. It’s about finding the judicious balance where the precision of terrain representation meets practical utility and adheres to budgetary realities. Map creators and users alike are encouraged to critically evaluate their specific needs and objectives. By doing so, they can move beyond the misconception that more detail automatically equates to a better map, instead choosing contour intervals that deliver the most effective and usable terrain representation in their topographical maps, ensuring clarity, accuracy, and true Cost-Effectiveness.

This strategic approach lays the groundwork for creating maps that are not only accurate but also truly effective tools for a myriad of applications.

Frequently Asked Questions About Smaller Contour Intervals: 7 Hidden Disadvantages Revealed!

When might smaller contour intervals be inappropriate?

Smaller contour intervals are not always better. In gently sloping terrain, they can create excessively dense contour lines, obscuring other map details. The increased complexity can actually reduce clarity.

How do smaller contour intervals affect map production costs?

Creating maps with smaller contour intervals typically involves more detailed surveying or higher-resolution data acquisition. This translates to significantly higher costs for both data collection and processing.

What issues arise when using smaller contour intervals with low-resolution data?

If the underlying data resolution is insufficient, smaller contour intervals may create artificial detail. This can lead to a false sense of accuracy and potentially misleading interpretations of the terrain. The disadvantages of using smaller contour intervals become more apparent.

How do smaller contour intervals impact map readability?

While providing more detail, excessively small contour intervals can clutter the map. This makes it difficult to distinguish important features and understand the overall terrain shape. Consider the disadvantages of using smaller contour intervals for the target audience.

In unraveling the paradox of Topographical Maps, we’ve explored seven compelling reasons why the pursuit of infinitesimally Smaller Contour Intervals can be counterproductive. From the immediate impact of severe Map Clutter and the risk of Terrain Misinterpretation to the escalating Survey Costs, the digital burden on Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the mismatch with Map Scale, and the high maintenance demands, it’s clear that more detail isn’t always the answer. We’ve shown how pushing the boundaries of precision can lead to diminishing returns, compromising both usability and Cost-Effectiveness.

The fundamental takeaway is this: selecting the optimal Contour Interval is a strategic decision, not a default one. It requires careful consideration of the map’s specific purpose, its intended audience, the viewing Map Scale, and your budgetary constraints. By prioritizing Map Readability, understanding the true Cost-Effectiveness of data collection, and critically evaluating the real-world utility of hyper-detailed Terrain Representation, we can move beyond mere precision to create truly effective, functional, and insightful Topographical Maps that serve their users best. Strike the balance, and unlock the true power of Cartography.