How Did the NAACP Ignite the Harlem Renaissance? Uncover the Secret!

When we picture the Harlem Renaissance, images of electrifying jazz, groundbreaking literature, and vibrant artistic expression often come to mind. This era was indeed a profound period of Black artistic and intellectual awakening, a cultural explosion that reshaped American identity. Yet, beyond the spotlight on individual geniuses and burgeoning cultural institutions, lies an often-underestimated architect: the NAACP.

Known primarily for its relentless legal advocacy and fight against racial injustice, the NAACP’s hand in sparking and sustaining this magnificent cultural movement is a story rarely fully told. How did an organization focused on civil rights also become a pivotal force in nurturing literary talent, advocating for artists, and creating the very landscape upon which the Renaissance thrived?

This article aims to peel back the layers, uncovering the specific initiatives and the profound, lasting legacy of the NAACP’s involvement, revealing five ‘secrets’ that cemented its role not just as a legal champion, but as a cultural catalyst.

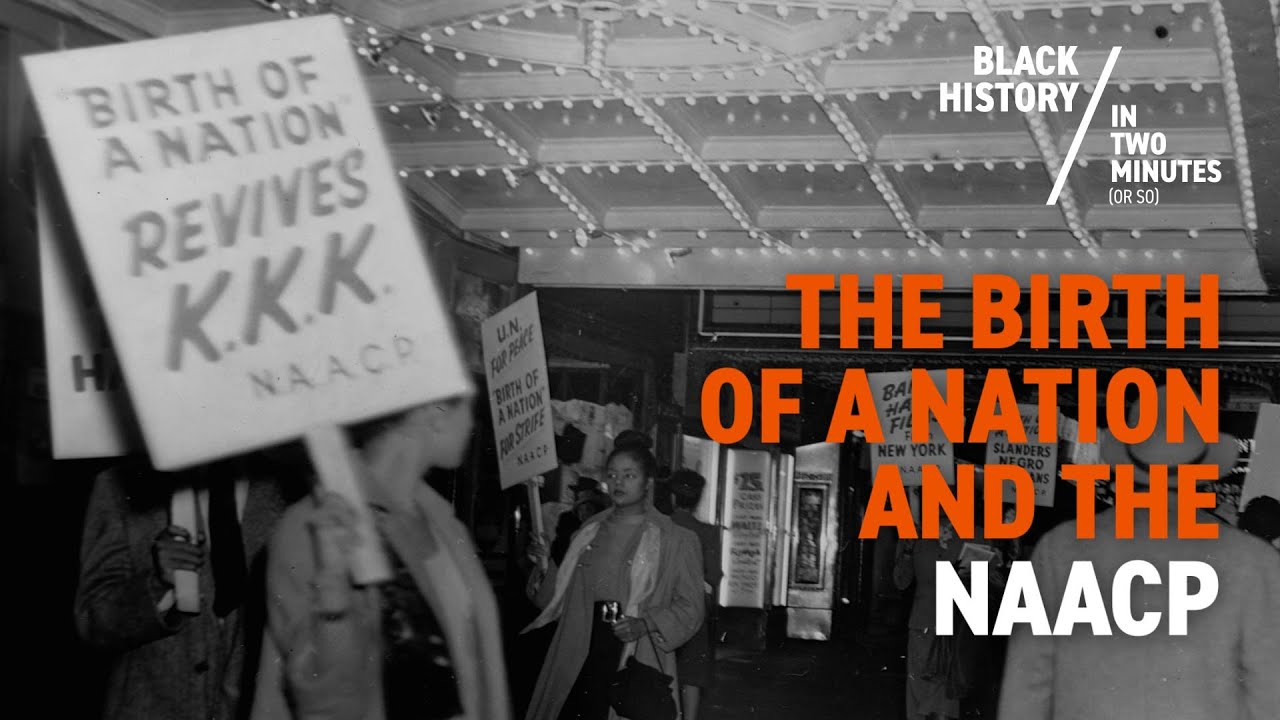

Image taken from the YouTube channel Black History in Two Minutes or so , from the video titled The Birth of a Nation & The Origins of the NAACP .

As the echoes of the Great Migration transformed urban landscapes, a new cultural and intellectual crescendo began to emerge, particularly within the bustling streets of New York City.

Beyond the Ballot Box: Unveiling the NAACP’s Unsung Role in the Harlem Renaissance

The early 20th century witnessed a transformative period in American history, characterized by profound social and cultural shifts. Amidst this upheaval, a groundbreaking movement took root in the vibrant neighborhood of Harlem, New York, giving rise to what we now know as the Harlem Renaissance.

A New Dawn: The Harlem Renaissance as a Cultural Crucible

The Harlem Renaissance was far more than just a fleeting artistic trend; it was a period of profound Black artistic and intellectual awakening that spanned the 1920s and early 1930s. This epoch saw an unprecedented explosion of creativity across literature, music, visual arts, and philosophy, primarily centered in Harlem. Black artists, writers, musicians, and thinkers coalesced, finding a powerful collective voice to express their experiences, challenge stereotypes, and redefine African American identity on their own terms. It was a moment of self-discovery and self-assertion, where the "New Negro" emerged, confident, articulate, and determined to shape their own narrative in a society grappling with racial prejudice.

The NAACP: A Vanguard for Justice in the Early 20th Century

Before delving into its cultural contributions, it’s crucial to understand the foundational mission of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Established in 1909, the NAACP quickly became a leading civil rights organization, primarily known for its unwavering commitment to racial equality through legal advocacy and direct action. Its core mission was, and remains, to secure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights in order to eliminate race-based discrimination and ensure the health and well-being of all persons. In the early 20th century, the NAACP was at the forefront of the fight against lynching, advocating for federal anti-lynching laws, challenging segregation in courts, and working to expand voting rights for African Americans across the nation.

More Than Legal Eagles: The NAACP’s Cultural Catalyst

While its legal battles and anti-lynching campaigns rightly dominate historical accounts, the pivotal role the NAACP played in fostering the Harlem Renaissance is often significantly underestimated. Beyond its primary legal advocacy, the organization understood that true liberation also required intellectual and cultural empowerment. The NAACP recognized that the arts could be a powerful tool for social change, challenging racist caricatures, promoting positive images of Black life, and inspiring pride within the community. Its leaders actively sought to cultivate and uplift Black talent, believing that artistic expression was an essential component of the broader struggle for civil rights. They were not merely observers of the cultural explosion but active architects, providing platforms, encouragement, and resources that proved indispensable to many emerging Black artists and intellectuals.

Our Journey Ahead: Uncovering the NAACP’s Enduring Legacy

This exploration aims to pull back the curtain on this often-overlooked facet of the NAACP’s history. Throughout this article, we will uncover the specific initiatives undertaken by the NAACP that directly contributed to the blossoming of the Harlem Renaissance. From publishing groundbreaking literature to sponsoring awards and fostering intellectual discourse, we will examine how this powerhouse organization extended its influence far beyond the courtroom. We will also delve into the lasting legacy of the NAACP’s involvement, demonstrating how its cultural stewardship laid critical groundwork for future generations of Black artists and activists.

One of the most significant and often celebrated examples of the NAACP’s commitment to nurturing Black voices was through its influential publication, The Crisis magazine.

The NAACP’s strategic foresight and dedicated efforts were instrumental in igniting the Harlem Renaissance, laying the groundwork for a cultural explosion that would redefine American identity.

The Inkwell of Revolution: How The Crisis Magazine Forged a Literary Generation

Among the NAACP’s most potent instruments in cultivating the Harlem Renaissance was The Crisis Magazine, a groundbreaking publication that transcended mere journalism to become a crucial literary and political journal. Under the visionary editorship of W. E. B. Du Bois, The Crisis was more than just a periodical; it was a vibrant forum where the complexities of Black American life were explored, debated, and celebrated. Du Bois, a towering intellectual and co-founder of the NAACP, meticulously curated content that not only advanced civil rights advocacy but also passionately promoted Black art, literature, and intellectual thought, setting a distinct tone for cultural discourse that championed racial pride and artistic excellence.

Jessie Redmon Fauset: The Literary Architect Behind the Scenes

While Du Bois provided the intellectual leadership, the crucial task of identifying and nurturing emerging literary talents often fell to Jessie Redmon Fauset, the magazine’s literary editor. Fauset, an accomplished novelist and poet in her own right, possessed an unparalleled eye for potential. She served as a meticulous gatekeeper and a generous mentor, reading countless submissions, offering constructive criticism, and tirelessly advocating for writers whose voices deserved national attention. Her discerning judgment and tireless dedication ensured that The Crisis consistently featured high-quality fiction, poetry, and essays, transforming it into an essential literary incubator.

A Launchpad for Legends: Giving Voice to a New Era

It was within the pages of The Crisis Magazine that many of the Harlem Renaissance’s most iconic figures first found their audience and national recognition. The magazine provided an invaluable platform for early works by literary giants such as Langston Hughes, whose evocative poetry captured the rhythms and spirit of Black America; Zora Neale Hurston, who would later redefine American literature with her nuanced portrayals of Southern Black life; and Countee Cullen, whose lyrical verses explored themes of race, identity, and beauty. For these burgeoning artists, The Crisis offered not just publication, but validation and the crucial exposure needed to launch their illustrious careers. The magazine became a beacon, signaling to the nation that a new, powerful literary movement was on the horizon, driven by Black voices.

Contrasting Contributions: The Crisis vs. Opportunity

While The Crisis played an undeniable role, it’s important to acknowledge other significant publications of the era, notably Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, published by the National Urban League. Both magazines were instrumental in fostering Black talent and intellectual discourse during the Harlem Renaissance, yet they approached their missions with distinct nuances. The Crisis, with its more direct ties to the NAACP’s civil rights agenda, often presented a more assertive and overtly political stance alongside its cultural offerings. Du Bois’s powerful editorial voice infused the magazine with an intellectual vigor that challenged racial norms and advocated for immediate social change. Opportunity, under the editorship of Charles S. Johnson, tended to focus more on sociological studies, economic empowerment, and community development, though it too hosted influential literary contests and provided a vital platform for writers. The NAACP’s distinct contribution through The Crisis lay in its bold integration of political activism with cultural promotion, demonstrating that the fight for civil rights was inseparable from the celebration and advancement of Black artistic and intellectual life.

A Comparison of Key Features: The Crisis vs. Opportunity during the Harlem Renaissance

| Feature | The Crisis Magazine (NAACP) | Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life (National Urban League) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Civil Rights Advocacy, Black Culture, Politics | Sociological Studies, Economic Empowerment, Black Culture |

| Key Editor(s) | W. E. B. Du Bois, Jessie Redmon Fauset | Charles S. Johnson (Editor), Alain Locke (Contributing) |

| Approach to Culture | Platform for Black voices, challenge norms | Documenting Black life, fostering artistic development |

| Literary Contests | Yes (e.g., Krigwa Players Awards) | Yes (e.g., Opportunity Literary Contests, well-known) |

| Overall Tone | Often more assertive, intellectual, polemic | More academic, sociological, fostering community dialogue |

| Primary Goal | Fight for equality, elevate Black intellectual/artistic life | Improve living conditions, provide economic opportunities, promote Black arts |

Beyond the pages of The Crisis, the NAACP further cemented its commitment to Black artists through prestigious awards and direct support.

Building on the foundation laid by publications like The Crisis Magazine, the NAACP understood that true upliftment required not just platforms for expression, but also direct recognition and strategic support for the community’s brightest minds.

Forging Stars: How the Spingarn Medal Illuminated Black Excellence and Fueled a Renaissance

While The Crisis Magazine offered a crucial literary launchpad, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) also pioneered a more direct form of patronage and recognition: the Spingarn Medal. Established in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, then Chairman of the NAACP’s board of directors, this prestigious award aimed "to call the attention of the American people to the existence of distinguished merit and achievement among American Negroes." It quickly became a pivotal tool for celebrating Black excellence and, by extension, nurturing the burgeoning talent of the Harlem Renaissance.

The Golden Standard: Establishing the Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal was conceived as an annual award to recognize the highest achievement of any African American. More than just an honor, it served several critical functions:

- National Recognition and Prestige: By bestowing a gold medal and a significant monetary prize (originally $1,000), the NAACP brought national attention to African American accomplishments that were often ignored or downplayed by mainstream society. This elevated the public perception of Black intellectual and artistic capabilities.

- Early Patronage: For many recipients, the award provided not only validation but also tangible support, acting as a vital form of early patronage. This recognition could open doors to further opportunities, funding, and a wider audience, directly contributing to the sustenance of Black artists, writers, and intellectuals.

- Counteracting Negative Stereotypes: In an era rife with racial prejudice, highlighting outstanding achievements by African Americans was a powerful counter-narrative, challenging prevailing stereotypes and fostering pride within the Black community.

The medal quickly became a beacon, signaling to the world that Black talent was not only present but thriving, laying essential groundwork for the cultural explosion known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Spotlighting Harlem’s Luminaries and Beyond

The Spingarn Medal recognized a diverse array of African American leaders, thinkers, and creators. During the Harlem Renaissance era, several individuals whose work defined the cultural movement were honored, showcasing the breadth of Black achievement:

| Year | Recipient | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | W. E. B. Du Bois | Co-founder of the NAACP, editor of The Crisis, influential scholar, writer, and civil rights leader who shaped the intellectual foundation of the Harlem Renaissance. |

| 1924 | Roland Hayes | Internationally acclaimed concert tenor, breaking racial barriers in classical music and inspiring a generation of Black artists. |

| 1925 | James Weldon Johnson | Celebrated poet, novelist, songwriter, and executive secretary of the NAACP; a key figure in promoting and nurturing Harlem Renaissance talent. |

| 1926 | Carter G. Woodson | Renowned historian, author, and founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, often called the "Father of Black History." |

| 1928 | Charles W. Chesnutt | Pioneering African American novelist and short story writer, whose realistic portrayals of Black life predated and influenced the Harlem Renaissance. |

These individuals represent just a few of the "stars" whose brilliance was acknowledged, demonstrating the medal’s role in affirming and amplifying Black contributions to American culture.

Direct Advocacy and the Role of James Weldon Johnson

Beyond the symbolic power of the Spingarn Medal, the NAACP engaged in direct advocacy for Black artists, often spearheaded by dynamic figures like James Weldon Johnson. Johnson, a celebrated writer, poet, and songwriter in his own right, served as an NAACP field secretary and later executive secretary. His unique position allowed him to:

- Bridge Gaps: Johnson masterfully navigated the worlds of activism and art, using his influence within the NAACP to promote budding talent. He understood that cultural expression was a potent form of protest and upliftment.

- Mentor and Promote: He actively championed emerging writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance, often using his networks to secure publishing deals, performance opportunities, and public recognition for them. His personal example, as a Black intellectual awarded the Spingarn Medal himself in 1925, inspired many.

- Advocate for Resources: Johnson and the NAACP worked to create spaces and opportunities for cultural expression in Harlem, New York, and beyond, advocating for funding, venues, and platforms where Black artists could showcase their work without compromise.

Influencing the “New Negro” Landscape

The NAACP’s broader advocacy efforts were instrumental in shaping the cultural landscape that characterized the Harlem Renaissance. By promoting intellectual discourse, supporting artistic endeavors, and creating opportunities for cultural expression, the organization significantly influenced landmark works like Alain Locke’s "The New Negro" (1925) anthology. This seminal text, often considered the definitive statement of the Harlem Renaissance, compiled essays, poetry, and fiction by Black writers and thinkers, presenting a powerful vision of a self-aware, culturally rich "New Negro." The NAACP’s consistent efforts to recognize and nurture genius directly contributed to the intellectual and artistic ferment that made such a collection possible, providing both the platform and the celebrated voices.

This blend of direct recognition and proactive support was crucial in cultivating a vibrant cultural scene, yet the battle for Black self-expression and equality extended far beyond the arts, demanding sustained political and legal advocacy.

While the NAACP directly celebrated Black achievement with awards like the Spingarn Medal, its most foundational work for the arts took place not in concert halls, but in the chambers of Congress and the nation’s courtrooms.

Before the Canvas, the Courthouse: How Legal Battles Built the Stage for a Renaissance

Art does not flourish in a climate of terror. For a culture to blossom, its people must first have the basic right to live without fear. The NAACP understood this deeply, recognizing that its political and legal advocacy was not a separate track from its cultural ambitions but the very bedrock upon which a new Black identity could be built. The fight for civil rights was, in essence, the fight to create a cultural landscape where the Harlem Renaissance could take root and grow.

The War on Terror: The Anti-Lynching Campaign

Long before artists could freely express themselves, the NAACP waged a relentless war against the most horrific form of racial terrorism in America: lynching. This was not merely a crime; it was a public spectacle of racial control designed to intimidate and brutalize the entire Black community.

The organization’s campaign was multifaceted and unyielding. It included:

- Investigation and Exposure: Publishing detailed, often gruesome, reports on lynchings to shock the conscience of the nation and the world.

- Public Awareness: Staging mass protests, such as the 1917 Silent Protest Parade in New York City, where 10,000 African Americans marched to protest racial violence.

- Legislative Action: The centerpiece of the campaign was the push for federal anti-lynching legislation. The NAACP was the primary force behind the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922 but was ultimately blocked in the Senate by a filibuster from Southern Democrats.

Though the Dyer Bill failed to become law, the campaign was a profound strategic victory. It dragged the brutal reality of lynching into the national spotlight, forcing a conversation that many Americans preferred to ignore and making it a central issue of the civil rights struggle.

From Safety to Self-Expression: Securing a Haven in Harlem

The NAACP’s fight against racial terrorism had a direct and tangible impact on cultural development. By challenging the systems that enabled mob violence, the organization helped create pockets of relative safety where Black communities could stabilize and thrive. Harlem, New York, became the most prominent example.

As the Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans to northern cities, the NAACP’s work helped ensure that these new urban centers would not replicate the overt racial terror of the South. This newfound security, however fragile, was essential. It meant that:

- Poets, painters, and musicians could gather in salons and speakeasies without the imminent threat of mob violence.

- Theaters like the Lafayette and the Apollo could become vibrant hubs for Black performance.

- Intellectuals and activists could debate and formulate new ideas for the future of the race.

Securing basic physical safety lowered the cost of existence, freeing up the emotional and psychological space necessary for creative and intellectual pursuits to flourish. The stability the NAACP fought for transformed places like Harlem from mere residential districts into world-renowned cultural capitals.

Walter White: The Investigator on the Front Lines

No individual better personified the link between the NAACP’s legal battles and its cultural goals than Walter Francis White. As an assistant secretary and later the head of the NAACP, White, who was fair-skinned with blonde hair and blue eyes, used his appearance to go undercover in the South and investigate lynchings. He would pass as white to gather firsthand information from perpetrators and witnesses, often at immense personal risk.

His meticulously detailed reports provided the undeniable evidence that fueled the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaigns and lobbying efforts. White’s work demonstrated that the fight for racial uplift was not an abstract legal exercise; it was a gritty, dangerous, and essential battle for survival. He understood that every legal brief filed and every politician lobbied was a direct contribution to a future where Black artists would have the freedom to create works that celebrated their humanity rather than just mourning their persecution.

The confidence and boldness that characterized the art of the Harlem Renaissance—the unapologetic celebration of Black life, beauty, and intellect—was not born in a vacuum. It was forged in the crucible of the NAACP’s political and legal victories, which proved that the old systems of oppression could be challenged and, one day, defeated.

With the physical and legal ground increasingly secured, the intellectual framework for this new cultural era was also being meticulously crafted by key thinkers within the organization.

While political advocacy laid the groundwork for a new cultural landscape for African Americans, the intellectual architects within the movement began to define its very spirit and direction, envisioning the path to true liberation and equality.

The Crucible of Intellect: How Du Bois Forged the Talented Tenth Ideal

At the dawn of the 20th century, as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took shape, it found a powerful intellectual anchor in the formidable figure of W. E. B. Du Bois. A towering scholar, sociologist, historian, and activist, Du Bois was not merely a participant but a principal ideologue who shaped the organization’s early vision and, by extension, the aspirations of an entire race. His leadership within the NAACP was characterized by an unwavering belief in intellectual excellence as a primary tool for racial upliftment, a concept most famously encapsulated in his articulation of the "Talented Tenth."

The Vision of the Talented Tenth

Du Bois posited that within the African American community, there existed a "Talented Tenth" – a cadre of exceptionally gifted individuals who, through higher education and cultural refinement, would serve as the vanguard of racial progress. This ideology was not an elitist dismissal of the broader Black population but rather a strategic call to action, recognizing that leadership, advocacy, and the creation of a distinct cultural identity required cultivated minds.

The "Talented Tenth" concept encouraged:

- Education and Cultivation: A rigorous focus on advanced education in universities and specialized training in various professions. This was seen as essential for developing individuals capable of critical thought, effective advocacy, and cultural innovation.

- Leadership of the Race: These educated individuals were expected to assume leadership roles across all spheres—politics, education, business, and especially arts and letters. They would guide their communities, articulate their needs, and represent Black interests on a national and international stage.

- Moral and Cultural Responsibility: Beyond intellectual prowess, the "Talented Tenth" bore the responsibility of upholding high moral standards and fostering cultural pride, serving as role models and champions of the race’s inherent dignity.

NAACP’s Ideological Framework: Art as Advocacy

The NAACP, heavily influenced by Du Bois’s vision, played a crucial role in operationalizing this ideological framework, particularly by positioning art and literature as indispensable tools for racial pride and challenging deeply entrenched stereotypes. The organization understood that legal and political battles alone were insufficient; a revolution in perception and self-identity was also necessary.

Through publications like The Crisis magazine, edited by Du Bois himself, the NAACP provided a platform where Black intellectuals, writers, and artists could share their work, articulate their perspectives, and directly confront the caricatures and prejudices prevalent in mainstream American society. The Crisis became more than a news publication; it was a cultural beacon, showcasing poetry, short stories, essays, and visual art that celebrated Black life and culture.

This strategic emphasis achieved several critical objectives:

- Challenging Stereotypes: By presenting nuanced, complex, and positive portrayals of Black characters and experiences, art and literature directly countered the racist stereotypes perpetuated in popular culture.

- Fostering Racial Pride: The celebration of Black history, heritage, and contemporary achievements through artistic expression instilled a sense of dignity and pride among African Americans.

- Humanizing the Black Experience: Art allowed for emotional connection and empathy, helping to demonstrate the shared humanity of Black Americans to a predominantly white audience.

Catalyst for the Harlem Renaissance

The intellectual framework provided by Du Bois and championed by the NAACP proved to be a powerful catalyst for the emerging generation of artists and thinkers who would come to define the Harlem Renaissance. By promoting the idea of the "Talented Tenth" and emphasizing the power of cultural expression, the NAACP helped to create an environment where these young talents felt empowered and purposeful.

For artists like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, and Aaron Douglas, the message resonated deeply: their artistic endeavors were not merely personal expression but vital contributions to a larger struggle for racial equality and self-determination. They were encouraged to embrace their unique cultural heritage, explore the complexities of Black identity, and articulate a vision for the future, free from the constraints of white expectations. This fostered a profound sense of racial identity and purpose, transforming Harlem into a vibrant intellectual and artistic hub where a new Black aesthetic flourished.

The vision articulated by Du Bois and championed by the NAACP was not confined to intellectual circles in Harlem, but sought a broader reach.

While W. E. B. Du Bois championed the "Talented Tenth" as the intellectual and artistic vanguard, it was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that provided the vital infrastructure to broadcast their brilliance far beyond the confines of Harlem.

Echoes Across the Nation: The NAACP’s Network Amplifying Harlem’s Cultural Resonance

The Harlem Renaissance, a vibrant explosion of Black creativity, was not an isolated phenomenon contained solely within a few blocks of New York City. Its ideas, artists, and cultural impact resonated across the United States, thanks in large part to the strategic and widespread efforts of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). More than a civil rights organization, the NAACP understood the power of culture as a tool for advocacy, dignity, and social change, meticulously building a national apparatus to amplify Black voices and ensure their work reached every corner of the nation.

A Web of Influence: The NAACP’s National Branch Network

By the time the Harlem Renaissance gained momentum, the NAACP boasted a robust national network of hundreds of local branches. These branches, operating in cities and towns far removed from Harlem, became crucial outposts for disseminating the movement’s artistic and intellectual output. They served as local cultural centers, extending the reach of Harlem’s artistic and intellectual ferment to communities where direct exposure might otherwise have been impossible. Each branch acted as a conduit, bringing the latest works of Black authors, the insights of Black intellectuals, and the spirit of Black artistry to diverse audiences. Through these decentralized yet coordinated efforts, the NAACP transformed what could have been a regional phenomenon into a truly national cultural awakening, fostering a shared sense of pride and cultural identity among African Americans nationwide.

Staging Excellence: Showcasing Black Artists and Intellectuals

A key strategy employed by the NAACP was the active promotion and showcasing of Black talent through various organized events. Their initiatives were designed not only to entertain but also to educate and inspire, introducing wider audiences to the richness and diversity of Black creative expression:

- Lectures and Speaking Tours: NAACP branches regularly hosted prominent Black intellectuals, writers, and artists from Harlem and beyond. Figures like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and W. E. B. Du Bois themselves embarked on speaking tours, sharing their work and perspectives with audiences in churches, community halls, and educational institutions across the country. These events provided direct engagement with the architects of the Renaissance, fostering dialogue and intellectual exchange.

- Literary Contests: The NAACP’s official magazine, The Crisis, under the editorship of W. E. B. Du Bois and later Charles S. Johnson, launched influential literary contests. These competitions provided vital platforms for emerging Black writers, offering recognition, publication, and prize money. By actively soliciting and promoting new works, The Crisis became a central clearinghouse for new literary talent, helping to launch the careers of many figures now recognized as giants of the Harlem Renaissance.

- Cultural Events and Exhibitions: Local branches organized art exhibitions, theatrical performances, and musical concerts, giving Black artists opportunities to display their work and perform for their communities. These events were instrumental in cultivating local artistic scenes and celebrating Black achievement in the arts, demonstrating that cultural excellence was not confined to major urban centers.

Partnerships and Parallel Paths: Working with the National Urban League

While the NAACP was a formidable force on its own, its efforts to promote Black culture often involved collaborations and, at times, friendly rivalries with other influential organizations. The National Urban League, for instance, shared many of the NAACP’s objectives regarding the advancement of African Americans, though their approaches often differed.

- Shared Vision: Both organizations recognized the critical role of cultural expression in challenging racial stereotypes and fostering Black pride. The Urban League, with its focus on economic opportunity and urban integration, often complemented the NAACP’s cultural advocacy by helping artists and writers secure housing, employment, and networking opportunities in cities.

- Collaborative Ventures: There were instances of direct collaboration, such as co-sponsoring events, publishing articles in each other’s journals (the Urban League had Opportunity magazine, a significant rival and partner to The Crisis), or advocating jointly for the inclusion of Black artists in mainstream institutions.

- Friendly Rivalries: The competition between The Crisis and Opportunity was particularly notable. This "friendly rivalry" spurred both publications to seek out and promote the most exciting new Black talent, arguably enriching the Harlem Renaissance more than if one organization had dominated the landscape. Each magazine strived to publish the best poetry, short stories, and essays, providing double the avenues for Black writers to get their work seen and celebrated.

Advocating for Mainstream Recognition: The NAACP’s Political and Social Capital

Beyond nurturing Black talent within its own network, the NAACP leveraged its growing political and social capital to advocate for the inclusion of Black artistic expression in mainstream American culture. This was a direct challenge to the pervasive racial segregation and exclusion that defined the era.

The NAACP understood that true equality meant not just legal rights but also the recognition and celebration of Black contributions to the national cultural fabric. They employed several strategies:

- Lobbying and Public Pressure: The organization exerted pressure on mainstream galleries, publishing houses, theaters, and academic institutions to feature and discuss Black artists. This often involved public campaigns, letters, and direct engagement with influential gatekeepers in the arts.

- Education and Awareness: The NAACP tirelessly worked to educate white audiences about the quality and significance of Black art, challenging preconceived notions and dismantling stereotypes through cultural exposure. By presenting Black artists as national treasures rather than niche curiosities, they aimed to integrate Black culture into the broader American narrative.

- Connecting Culture to Civil Rights: For the NAACP, cultural advocacy was not separate from their civil rights agenda; it was an integral part. By demonstrating the profound artistic and intellectual capabilities of Black Americans, they provided powerful counter-arguments to racist ideologies that underpinned segregation and discrimination. Showcasing Black brilliance was a direct assault on the notion of Black inferiority, thereby advancing the cause of racial justice.

The NAACP’s multifaceted efforts in cultural advocacy laid a robust foundation, the ripples of which would be felt for generations to come.

As the NAACP strategically expanded its network and influence far beyond the vibrant streets of Harlem, its profound impact wasn’t solely political or legal; it deeply permeated the cultural fabric of a nation, laying groundwork for artistic and social transformation.

The Unseen Hand: How the NAACP’s Cultural Advocacy Forged a Legacy

The story of the Harlem Renaissance, often celebrated as a vibrant explosion of Black artistic and intellectual life, cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) pivotal, often unseen, role. Far from being a mere spectator, the NAACP acted as a crucial architect, providing the platforms, recognition, and political stability necessary for this cultural flourishing to take root and thrive.

Nurturing the Renaissance: Platforms and Protection

The NAACP understood that true liberation required not just legal battles but also a profound shift in societal perception. To this end, its flagship publication, The Crisis magazine, under the astute editorship of W.E.B. Du Bois, became an indispensable conduit for emerging Black writers, poets, and artists. Through its pages, The Crisis offered:

- A National Platform: It published new works, reviews, and essays by authors like Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Zora Neale Hurston, granting them a national audience and critical recognition often denied by mainstream publications.

- Literary Contests and Awards: The magazine initiated literary prizes, actively scouting and encouraging new talent, thereby validating Black artistic expression and offering tangible incentives for creation.

- Intellectual Discourse: The Crisis fostered a robust intellectual environment, where the ideas of the "New Negro" — an assertive, self-defined Black identity — could be debated and disseminated, providing a philosophical backbone for the cultural movement.

Beyond publishing, the NAACP provided a degree of political stability and protection. By consistently challenging racial discrimination, fighting for voting rights, and advocating for civil liberties, the organization created a slightly more permissive, if still deeply prejudiced, environment where Black artists could express themselves with a newfound sense of agency, knowing there was a powerful organization working to defend their fundamental rights.

From Cultural Awakening to Civil Rights Action

The vibrant cultural flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance was not an isolated artistic phenomenon; it was inextricably linked to the subsequent Civil Rights Movement. The NAACP’s support for the Renaissance directly contributed to this connection in several ways:

- Building Racial Pride and Identity: The art, literature, and music of the Renaissance celebrated Black culture, history, and resilience. This cultivation of racial pride and a positive self-image was crucial in galvanizing a community to demand its rights. When people see their culture elevated and affirmed, they are more empowered to fight for their political and social standing.

- Challenging Stereotypes: Renaissance artists, with the NAACP’s backing, directly countered dehumanizing caricatures of Black people prevalent in American society. They presented complex, multifaceted Black characters and narratives, chipping away at the racist foundations that underpinned segregation and discrimination. This cultural re-education was a prerequisite for challenging legal inequalities.

- Inspiring Future Activists: Many figures who would become central to the Civil Rights Movement grew up witnessing or participating in the cultural shifts initiated by the Harlem Renaissance. The sense of possibility and the articulation of a distinctly Black voice provided a powerful wellspring of inspiration for direct action and political organizing in the decades to follow.

An Indelible Mark on Black Artistic Expression

The NAACP’s initiatives left an indelible mark on Black artistic expression and its place in American history. By legitimizing Black voices and ensuring their visibility, the organization helped to:

- Integrate Black Art into American Culture: It pushed for Black art to be recognized not as a niche, segregated genre, but as an essential and vital component of the broader American cultural tapestry.

- Establish a Tradition of Activist Art: The NAACP fostered an environment where art was understood not just for aesthetic pleasure, but also as a powerful tool for social commentary, protest, and advocacy – a tradition that continues in various forms today.

- Create Institutional Support: By establishing platforms and encouraging critical engagement, the NAACP demonstrated the crucial role that institutional support plays in nurturing and sustaining minority artistic movements.

The Ongoing Importance of Advocacy

The enduring legacy of the NAACP’s cultural advocacy underscores the ongoing importance of organizations dedicated to fostering cultural and political landscapes that support minority voices. In a world still grappling with issues of representation, equity, and systemic bias, groups like the NAACP remain critical for:

- Ensuring Diverse Representation: Continuing to champion the inclusion of minority artists and narratives in all forms of media and education.

- Protecting Creative Freedom: Advocating for the rights of artists to express themselves without fear of censorship or discrimination.

- Bridging Culture and Policy: Understanding that cultural shifts often precede, or are essential for, meaningful political and social change.

- Mentoring New Voices: Providing platforms, mentorship, and resources for the next generation of minority artists and cultural leaders.

The NAACP’s early commitment to nurturing Black artistic voices thus serves as a powerful testament to the intertwined nature of cultural and political liberation, a principle that continues to guide its mission in an ever-evolving world.

Frequently Asked Questions About the NAACP and the Harlem Renaissance

What was the NAACP’s primary role during the Harlem Renaissance?

The NAACP acted as a crucial institutional supporter and platform for the movement. It used its influence and resources to promote Black artists, writers, and intellectuals, giving them national visibility and legitimacy.

How did the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, contribute?

The Crisis, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois, was a premier outlet for Harlem Renaissance talent. It regularly published the works of poets like Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, showcasing Black literary excellence to a wide audience and sponsoring literary contests.

In what ways did the NAACP’s political activism support the arts?

The NAACP’s fight against racial injustice created a climate of Black pride and resistance that fueled artistic expression. This political foundation is fundamental to understanding how the NAACP played an important role in the Harlem Renaissance, as it gave artists the confidence to explore complex themes of identity and struggle.

Did the NAACP directly sponsor artists and events?

Yes, the organization sponsored awards and events to celebrate Black achievement. The annual Spingarn Medal, for example, honored key figures who contributed to the era’s cultural and intellectual life, providing crucial patronage and recognition for the movement’s leaders.

In shedding light on these ‘secrets,’ we recognize that the NAACP’s role in the Harlem Renaissance was far more expansive than commonly understood. From the literary launchpad of The Crisis Magazine to the prestige of the Spingarn Medal, from relentless anti-lynching campaigns that forged a safer environment for expression, to the intellectual architecture provided by W. E. B. Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth” ideal, and its extensive national network amplifying voices, the NAACP was a multifaceted engine of cultural progress.

Its initiatives provided the essential platforms, crucial recognition, and political stability necessary for the profound cultural flourishing we celebrate today. The vibrant self-expression of the Harlem Renaissance, nurtured in part by the NAACP, laid an indelible mark on Black artistic expression and its rightful place in American history, directly connecting to the subsequent Civil Rights Movement. Indeed, the legacy of the NAACP’s cultural advocacy continues to underscore the vital importance of organizations dedicated not only to legal justice but also to fostering inclusive cultural and political landscapes where all voices can thrive.