From Decimal to Whole: 3 Easy Methods You Should Know Now!

Ever found yourself needing to simplify a messy decimal, perhaps for a financial report, a user interface, or a crucial calculation? The jump from a precise decimal to a clean whole number might seem straightforward, but it’s a critical step that can significantly impact the accuracy and integrity of your data. Maintaining precision while converting floating-point numbers to integers is a common challenge across countless real-world applications.

But what if there were clear, easy-to-understand methods to bridge this gap effectively? This article will guide you through three fundamental approaches: Rounding, Truncation, and the powerful Ceiling/Floor functions. By diving deep into each algorithm, you’ll gain the knowledge to confidently choose the right method for any specific scenario, ensuring your financial calculations are spot-on and your user interfaces are flawlessly displayed. Get ready to master the art of decimal-to-whole number conversion!

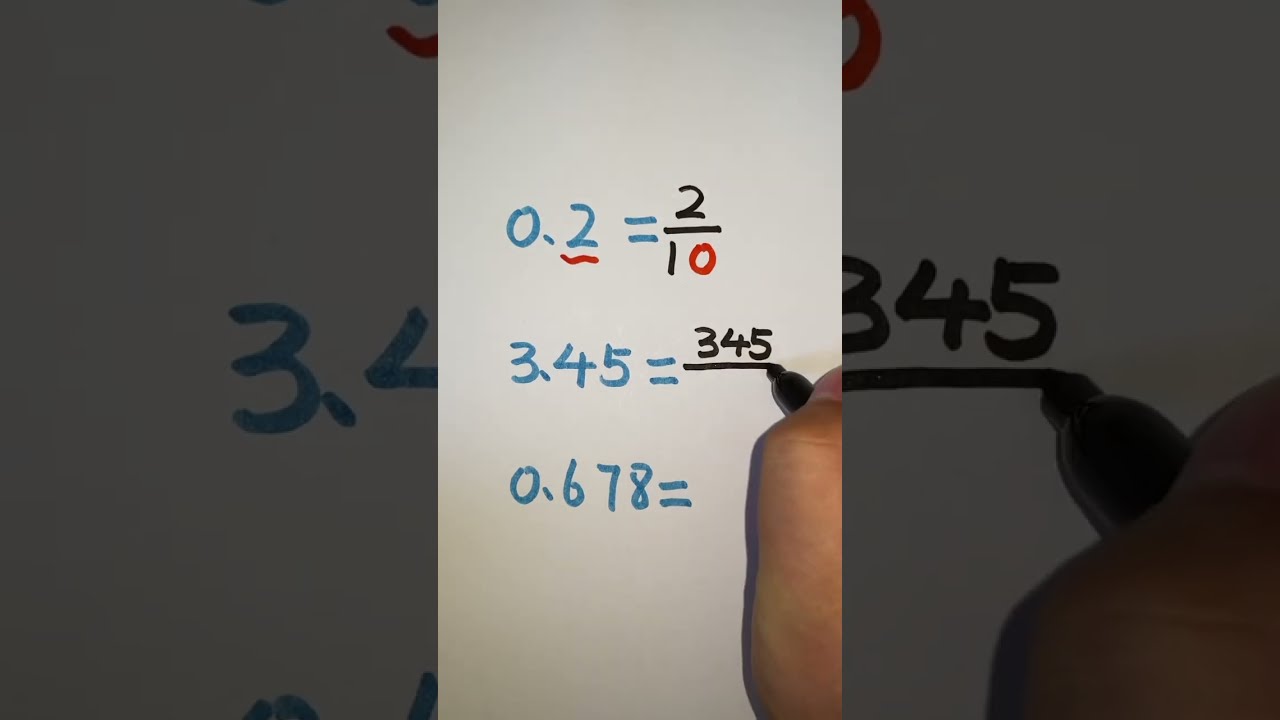

Image taken from the YouTube channel Math Tricks , from the video titled How to convert decimals to fractions | Converting decimal to fraction #decimal #decimals #shorts .

While managing diverse forms of numerical data is a constant in many fields, we frequently encounter scenarios where a number’s exact form needs to change to fit specific requirements.

In our increasingly data-driven world, decimal numbers are ubiquitous, representing everything from financial transactions to scientific measurements. However, there are countless real-world applications where these fractional components become either irrelevant, impractical, or even problematic. The need to convert a decimal number into a whole number or integer is a common operational requirement across various domains.

Why the Conversion is Crucial: Real-World Applications

Imagine a financial ledger that needs to display only whole dollar amounts, or an inventory system tracking physical items that cannot exist in fractions. Consider a user interface where displaying "3.75" tasks completed might be less intuitive than "4" tasks, or a sensor output that requires discrete integer values for further processing. From calculating the number of complete units that can be purchased with a given budget to determining the number of full days elapsed in a period, the transformation from a decimal to an integer is an essential step in data processing.

Common Scenarios Requiring Conversion:

- Financial Calculations: Ensuring currency amounts are presented as whole units (e.g., dollars, euros) for clear reporting and preventing fractional cents.

- Inventory Management: Counting discrete physical items (e.g., no half-products or partial stock).

- User Interface (UI) Display: Presenting cleaner, more readable numbers to users, such as progress bars or item counts.

- Statistical Analysis: Grouping data into whole categories or counting discrete occurrences.

- Resource Allocation: Determining the number of full resources (e.g., employees, machines) needed or available.

The Inherent Challenge: Precision and Accuracy

While the goal of converting a decimal to a whole number seems straightforward, the process is fraught with the challenge of maintaining precision and accuracy. A decimal number inherently carries more information than its integer counterpart. When we remove the fractional part, we inevitably lose some degree of information. The critical question becomes: how do we manage this loss of information responsibly, ensuring the resulting whole number accurately reflects the original value’s intent within the specific context?

An incorrect conversion method can lead to significant issues, from minor display inconsistencies to major financial miscalculations. For instance, always rounding down in a financial context might lead to underreporting, while always rounding up could lead to overestimation. The choice of conversion method directly impacts the integrity and utility of the transformed data.

Navigating the Transformation: Three Core Methods

To address these challenges and provide robust solutions for various scenarios, this guide will explore three easy methods for converting decimal numbers into whole numbers or integers. Each method employs a distinct algorithm to handle the fractional component, yielding different results depending on the input and the desired outcome:

- Rounding: The most commonly understood method, aiming to find the nearest whole number.

- Truncation: Simply discarding the fractional part, effectively rounding towards zero.

- Ceiling/Floor Functions: Specifically designed to always round up (ceiling) or always round down (floor) to the nearest integer.

The Importance of Informed Choice

Understanding each of these algorithms is paramount. There isn’t a single "best" method; the optimal choice is always dictated by the specific context and the implications of the conversion. What works perfectly for a user interface display, prioritizing readability, might be entirely inappropriate for sensitive financial calculations where accuracy and specific accounting rules are non-negotiable. Similarly, a method suitable for resource allocation might differ from one used in scientific data aggregation.

By delving into the mechanics and appropriate use cases for each method, you will be equipped to make an informed decision, ensuring that your data type conversions are not just functional, but also precise and accurate for their intended purpose, from financial ledgers to intuitive application displays.

Let’s begin our exploration by examining the foundational technique of rounding, a method frequently employed to approximate the nearest integer.

While there are several ways to bridge the divide between decimal and whole numbers, the most familiar approach is rounding, a method that seeks the closest integer value.

Smoothing the Edges: How Rounding Simplifies Decimals

Rounding is the process of adjusting a decimal number to a nearby, simpler value—most often, the nearest whole number or integer. Think of it as finding the closest whole number landmark on a number line. If a decimal is slightly past the halfway point between two integers, it gets "pulled" toward the next one. If it hasn’t reached that halfway mark, it falls back to the previous one. This method is fundamental for making numbers more manageable and presentable without losing significant value.

The Rules of the Game: Common Rounding Methods

While the concept seems simple, the exact rule for handling the "halfway" point (like 2.5) can vary. The two most common methods have different strengths and are used in different contexts.

Standard Rounding (Round Half Up)

This is the rounding method most of us learn in school. The rule is straightforward:

- If the decimal part is 0.5 or greater, round up to the next whole number.

- If the decimal part is less than 0.5, round down to the current whole number.

Examples:

8.7is rounded up to9because .7 is greater than .5.8.2is rounded down to8because .2 is less than .5.8.5is rounded up to9because the rule includes the halfway point.

This method is intuitive and widely used, but over a large set of numbers, it can introduce a slight upward bias because the halfway point always rounds in one direction (up).

Banker’s Rounding (Round Half to Even)

Also known as "round half to nearest, ties to even," this method is common in financial and scientific applications where minimizing bias is critical. The rule adds a condition for the halfway point:

- If the decimal part is greater than 0.5, round up.

- If the decimal part is less than 0.5, round down.

- If the decimal part is exactly 0.5, round to the nearest even whole number.

Examples:

3.5is rounded up to4(the nearest even integer).6.5is rounded down to6(the nearest even integer).7.7is still rounded up to8(since .7 is greater than .5).

By rounding the halfway point up sometimes and down other times, Banker’s Rounding helps to cancel out the upward bias seen in the standard method, leading to greater overall accuracy in large datasets.

Comparing the Methods: A Head-to-Head Look

The primary difference between these methods only appears with numbers ending in exactly .5. The table below illustrates how each rule treats various floating-point numbers.

| Decimal Number | Standard Rounding (Round Half Up) | Banker’s Rounding (Round Half to Even) |

|---|---|---|

| 4.2 | 4 | 4 |

| 4.8 | 5 | 5 |

| 4.5 | 5 | 4 |

| 5.5 | 6 | 6 |

| -2.5 | -3 | -2 |

Rounding in the Real World

Rounding is not just an academic exercise; it is an essential tool for presenting data clearly and efficiently in various fields.

- Financial Calculations: When you see a price like

$29.99, you are seeing a rounded value. Internally, a financial system might calculate a value to many decimal places (e.g.,$29.98754), but for display and final billing, it is rounded to the standard currency format (e.g., two decimal places). Banks and financial institutions often use Banker’s Rounding for their internal calculations to ensure fairness and accuracy over millions of transactions. - User Interface (UI) Display: In software and web design, precision can be overwhelming. A social media app might display "1.2k likes" instead of "1,248 likes" to keep the interface clean. Similarly, a battery indicator shows "87%" instead of a more precise but distracting "87.345%." Rounding simplifies information, reducing cognitive load for the user.

Rounding in Code: A Look at Programming Languages

How a computer handles rounding depends on the programming language and the specific functions used. This is a critical detail for developers to be aware of, as unexpected rounding behavior can lead to subtle bugs.

For example:

- Python 3’s built-in

round()function uses Banker’s Rounding (round half to even) as its default.round(2.5)will result in2, whileround(3.5)will result in4. - JavaScript’s

Math.round()function uses the standard "round half up" method.Math.round(2.5)will result in3.

Most languages provide a library of math functions that allow developers to explicitly choose how they want to round (e.g., always up, always down, or toward a specific rule), giving them full control over numerical precision.

But what if instead of finding the nearest whole number, you simply wanted to discard the decimal part altogether?

While rounding intelligently finds the closest whole number, sometimes a more direct and decisive approach is needed to handle decimal values.

The Truncation Cut: Simply Ignoring Everything After the Decimal

Where rounding analyzes a number’s fractional part to make a decision, truncation takes a much more straightforward path. It is the process of removing, or "cutting off," the entire fractional component of a decimal number, leaving only the integer part behind. Think of it as a clean slice right at the decimal point—everything to the right is simply discarded without consideration.

How Truncation Differs from Rounding

The fundamental difference between these two methods lies in how they handle the fractional value. Rounding looks at the fraction to determine whether to move to the higher or lower integer, aiming for the closest value. Truncation, on the other hand, is completely indifferent to the fractional part’s magnitude. It doesn’t find the nearest integer; it simply reveals the integer that is already there.

This leads to a critical distinction in behavior: truncation always moves the number towards zero.

- For a positive number, truncating is the same as always rounding down (e.g.,

8.99becomes8). - For a negative number, truncating is the same as always rounding up (e.g.,

-8.99becomes-8).

This predictable, direction-based behavior is one of its core features.

A Visual Comparison: Truncation vs. Rounding

The potential for a significant loss of accuracy with truncation becomes clear when you compare it directly with standard rounding. A number like 9.99 is extremely close to 10, but truncation disregards this proximity entirely.

The table below illustrates how these two methods handle the same set of decimal numbers.

| Original Number | Truncated Result (Towards Zero) | Standard Rounded Result (Nearest Integer) |

|---|---|---|

9.85 |

9 |

10 |

9.21 |

9 |

9 |

-9.85 |

-9 |

-10 |

-9.21 |

-9 |

-9 |

4.5 |

4 |

5 |

-4.5 |

-4 |

-4 |

Notice how for negative numbers, the results can be quite different. Truncating -9.85 yields -9, while rounding it produces -10. This highlights that truncation isn’t just "rounding down"—its behavior depends on the sign of the number.

Real-World Applications: Where Truncation Makes Sense

Despite its apparent disregard for mathematical precision, truncation is not a flawed method; it’s a specialized tool used when the underlying goal is not approximation but rather a clean separation of the integer and fractional parts.

-

Programming and Data Type Conversion: This is one of the most common applications. In many programming languages (like C++, Java, and Python), when you perform an explicit data type conversion from a floating-point number (like a

floatordouble) to an integer (int), the default behavior is truncation. This is because it is a computationally fast and unambiguous operation. The system doesn’t need to perform any logic; it just discards the bits representing the fractional part.// Example in a C-like language

float myFloat = 7.89;

int myInt = (int)myFloat; // myInt is now 7, not 8 -

Data Processing and Reporting: In certain scenarios of data processing, only the whole number part is fundamentally relevant. For example:

- Calculating Age: If a calculation determines someone is 35.8 years old, you would typically report their age as 35. You only care about the number of full years completed.

- Inventory Management: If you can fit 12 items in a box and have 150 items in stock, dividing

150 / 12gives you12.5. Truncating this to12tells you that you can fill exactly 12 full boxes. The remaining0.5represents a partial box, which is irrelevant to the count of completed units.

But what if your goal isn’t just to drop the decimal or find the nearest whole number, but to purposefully control the direction of the conversion, always rounding up or always rounding down?

While truncation offers a simple cut to a whole number by simply discarding decimal places, often you need more nuanced control, explicitly dictating whether a number should be rounded up or down.

The Digital Compass: Guiding Your Numbers Up or Down with Ceiling and Floor Functions

When a straightforward cut isn’t precise enough, or standard rounding doesn’t quite meet the requirement, mathematical functions like Ceiling and Floor provide the exact directionality needed for converting decimal numbers into whole numbers. These functions act as a digital compass, always pointing your number either directly "up" or firmly "down" to the nearest integer.

Understanding the Ceiling Function (Ceil)

The Ceiling function, often denoted as ceil(x) or ⌈x⌉, is a mathematical operation that rounds a given decimal number up to the nearest whole number or integer. Think of it as always reaching for the sky; no matter how small the decimal part, it pushes the number to the next highest integer. If the number is already a whole number, the Ceiling function returns the number itself.

- How it works:

ceil(3.1)becomes4(rounds up to the next integer).ceil(3.9)also becomes4(rounds up, regardless of how close it is to the next whole number).ceil(3.0)remains3.

Exploring the Floor Function (Floor)

Conversely, the Floor function, denoted as floor(x) or ⌊x⌋, is a mathematical operation that rounds a given decimal number down to the nearest whole number or integer. Imagine you’re always dropping to the ground; it takes any number with a decimal part and pulls it down to the next lowest integer. If the number is already a whole number, the Floor function returns the number itself.

- How it works:

floor(3.1)becomes3(rounds down to the previous integer).floor(3.9)also becomes3(rounds down, regardless of how close it is to the next whole number).floor(3.0)remains3.

Positive and Negative Floating-Point Numbers: Consistent Direction

The beauty of Ceiling and Floor functions lies in their consistent ‘up’ or ‘down’ directionality, which holds true even with negative floating-point numbers. It’s crucial to understand that "up" means towards positive infinity, and "down" means towards negative infinity.

- With Positive Numbers:

ceil(5.2)=6(up towards positive infinity)floor(5.2)=5(down towards negative infinity)

- With Negative Numbers:

ceil(-5.2)=-5(up towards positive infinity; -5 is greater than -5.2)floor(-5.2)=-6(down towards negative infinity; -6 is less than -5.2)

This distinct behavior, particularly with negative numbers, differentiates them sharply from standard rounding or truncation, which can sometimes produce counter-intuitive results depending on how they handle negative values.

A Comparative Look: Ceiling, Floor, and Standard Rounding

To illustrate the precise differences, let’s compare the results of the Ceiling function, Floor function, and standard rounding for various positive and negative decimal numbers. Standard rounding typically rounds to the nearest integer, with .5 usually rounding up.

| Original Number | Ceiling Function (Up) | Floor Function (Down) | Standard Rounding (Nearest) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 3.5 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.9 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 0.7 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| -0.7 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

| -3.1 | -3 | -4 | -3 |

| -3.5 | -3 | -4 | -4 |

| -3.9 | -3 | -4 | -4 |

This table clearly shows how ceil always moves towards a larger number (or stays the same), floor always moves towards a smaller number (or stays the same), and rounding aims for the closest integer, often using specific rules for .5 values.

Real-World Applications: Where Precision Matters

The precise, directed nature of Ceiling and Floor functions makes them invaluable in numerous real-world and computational scenarios:

- Resource Allocation: When you need to ensure you have at least enough of something, even if the calculation is fractional. For example, if you need 3.2 servers, you

ceil(3.2)to4to avoid a shortage. Similarly, if you need 2.8 boxes, you orderceil(2.8)=3boxes. - Calculating Batches or Units: For manufacturing, if a machine can produce 10.5 units per hour,

floor(10.5)=10tells you the completed units. If you need to know how many production runs are required to make a certain total, you might use ceiling. - Data Processing Scenarios:

- Time Intervals: If you’re scheduling events every half-hour and an event starts at

10:17, you mightceilit to the next half-hour (10:30) to determine the start of a reporting period. - Setting Bounds: Establishing strict upper (

ceil) or lower (floor) limits in data ranges or statistical bins. - Pagination: Calculating the total number of pages needed for a list of items (

ceil(totalitems / itemsper_page)).

- Time Intervals: If you’re scheduling events every half-hour and an event starts at

- Inventory Management: Ensuring minimum stock levels are met.

- Financial Calculations: While often requiring specific rounding rules, in some cases,

floormight be used for calculating full units of currency or items, andceilfor minimum payment thresholds.

Ubiquity in Programming

Given their clear utility, Ceiling and Floor functions are fundamental mathematical operations widely available across virtually all modern programming languages. You’ll find them as built-in functions in standard math libraries, such as math.ceil() and math.floor() in Python, ceil() and floor() in C++, Java, JavaScript, C#, and many others. Their consistent behavior makes them reliable tools for data type conversion, ensuring numerical precision in algorithm design, and solving a multitude of computational problems requiring strict upper or lower bounds.

Mastering these distinct methods provides a powerful toolkit, but knowing when and why to use each one is paramount, leading us to consider the broader implications of application, precision, and error handling.

Having explored the mechanics of Rounding, Truncation, and Ceiling/Floor functions, we now stand at a critical juncture: understanding how to apply these powerful tools judiciously.

Precision, Purpose, and Pitfalls: Deciding Your Decimal Conversion Strategy

The journey from a decimal number to its whole number representation is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. While each method—Rounding, Truncation, and Ceiling/Floor—effectively converts a decimal, their underlying logic and impact on the resulting value differ significantly. Choosing the "right" method is paramount, as it directly influences the accuracy, integrity, and ultimate correctness of your data processing. This decision hinges entirely on the specific scenario, the required level of precision, and the acceptable margin of accuracy for the task at hand.

The Crucial Triangle: Scenario, Precision, and Accuracy

Before implementing any conversion, it’s essential to analyze these three interconnected factors:

- Specific Scenario/Application: What is the real-world context of the number? Is it a monetary value, a count of items, a measurement, or a display element? Each context implies different expectations for whole number representation.

- Required Precision: How close does the converted whole number need to be to the original decimal? Does a small deviation matter, or is an approximation sufficient?

- Acceptable Accuracy/Error Margin: What are the consequences of any deviation? Can a number be slightly off without adverse effects, or must it be perfectly aligned with a specific rule (e.g., always rounding up for safety)?

These considerations guide you toward the most appropriate method, ensuring your algorithm behaves as intended and your data remains reliable.

Implications for Error Handling and Data Correctness

Each conversion method introduces its own set of implications for potential errors and the overall correctness of data:

- Rounding: Generally considered the "fairest" method, as it aims to minimize the average error over a large dataset by distributing deviations upwards and downwards. However, it can still lead to cumulative errors if not carefully managed, especially in chained calculations where small errors compound. Its neutrality makes it suitable for many general-purpose calculations where neither overestimation nor underestimation is systematically preferred.

- Truncation (or Flooring towards zero): This method consistently discards the fractional part, always reducing the magnitude of positive numbers and increasing the magnitude of negative numbers (i.e., moving towards zero). While simple and fast, it introduces a systematic bias (always underestimating positive values, always overestimating negative values). This bias can be problematic in financial calculations or resource allocation where consistent underestimation could lead to shortfalls. It’s a "safe" choice only when explicitly needing to disregard fractions without bias concern, or when speed is paramount and its specific bias is understood and accepted.

- Ceiling/Floor Functions: These methods are designed for specific directional rounding.

Ceilingalways rounds up, which is ideal for scenarios where you need to ensure sufficient resources (e.g., allocating full units).Flooralways rounds down, useful when you need to calculate the minimum number of full units available. Their directed nature means they introduce a predictable bias (always up or always down), which, unlike truncation’s general bias, is often desired and integral to the logic of the specific application. When used correctly, they prevent specific types of errors (e.g., insufficient stock, not enough capacity).

Understanding these inherent biases and error profiles is crucial for robust algorithm design. A choice made without this understanding can lead to subtle but significant inaccuracies, system failures, or incorrect financial outcomes.

Practical Examples: Context Dictates the Choice

Let’s illustrate these principles with real-world scenarios:

Financial Calculations: Where Precision is Paramount

Consider calculating interest, taxes, or currency conversions. In these scenarios, Rounding to the nearest whole unit (or a specified decimal place) is almost always preferred:

- Scenario: Calculating tax owed on an item costing $19.99 with a 7% tax rate.

- Calculation: $19.99 * 0.07 = $1.3993

- Rounding (to nearest cent): $1.40

- Truncation: $1.39

- Ceiling: $1.40

- Floor: $1.39

- Outcome: For tax collection,

Rounding(orCeilingin some specific tax regulations that always round up) is typically used to ensure fairness and prevent systematic under-collection or over-collection over many transactions. UsingTruncationwould consistently result in a slight loss for the tax authority or merchant.

User Interface (UI) Display: Simplicity and Readability

For displaying numbers to users, especially when exactness isn’t critical, the method might prioritize simplicity or a specific user experience:

- Scenario: Displaying the number of items in a shopping cart that has a fractional quantity (e.g., 2.75 items due to bundles or measurement).

- Calculation: 2.75 items

- Rounding: 3 items (User might perceive 3 items are present)

- Truncation: 2 items (User might think only 2 full items are present)

- Ceiling: 3 items (User might perceive 3 items are present)

- Floor: 2 items (User might think only 2 full items are present)

- Outcome: If the UI needs to show "how many full items you have,"

TruncationorFloormight be appropriate. If it’s "approximately how many items,"Roundingis suitable. If it’s "how many slots will this take up,"Ceilingmight be used. The choice here is driven by how the user should interpret the displayed number, not strict mathematical precision.

Resource Allocation and Capacity Planning: Guaranteeing Sufficiency

In situations where you need to ensure you have enough of something, rounding up is often the safest bet:

- Scenario: Determining the number of servers needed for 27.3 active users, where each server can handle 10 users.

- Calculation: 27.3 users / 10 users/server = 2.73 servers

- Rounding: 3 servers

- Truncation: 2 servers (Insufficient capacity)

- Ceiling: 3 servers (Sufficient capacity)

- Floor: 2 servers (Insufficient capacity)

- Outcome: Using

Ceilingensures you always provision enough servers to handle all users, preventing service degradation.TruncationorFloorwould lead to an under-provisioned system and unhappy users.

Decision Matrix: Selecting Your Whole Number Conversion Method

To aid in making these critical choices, consider the following decision matrix based on your real-world application and desired outcomes:

| Application/Desired Outcome | Priority | Recommended Method(s) | Rationale & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Calculations (e.g., taxes, interest, currency) | Minimizing average error, legal compliance, fairness | Rounding | Ensures balanced distribution of error over many transactions. Often mandated by financial regulations. Avoids systematic over/under-collection. Precision to specific decimal places (e.g., 2 for cents) is common. |

| Resource Allocation (e.g., servers, materials, vehicles) | Ensuring sufficiency, preventing shortages, safety | Ceiling | Guarantees enough units are always provisioned to meet demand, even if the demand is fractional. Prevents critical under-provisioning. |

| Counting Full Units (e.g., whole items, completed cycles) | Disregarding partial units, establishing a minimum | Truncation / Floor | Ideal when only complete units are relevant. Truncation (towards zero) is simple and fast. Floor guarantees rounding downwards irrespective of sign. Be aware of potential systematic bias if not explicitly desired. |

| General Display (e.g., progress bars, approximate counts) | Readability, simplicity, visual appeal, user expectation | Rounding / Truncation | Often less critical for exact mathematical precision. Rounding for a natural approximation. Truncation for simplicity or when showing "at least X." Choice depends on how the user is expected to interpret the number. |

| Performance Critical (when bias is acceptable) | Speed of operation | Truncation | Simplest and fastest method as it merely removes the fractional part. Only suitable when the inherent bias (always down for positive, up for negative) is understood and explicitly acceptable or negligible for the application. |

| Specific Rule Adherence (e.g., "always round up" for certain metrics) | Strict rule enforcement | Ceiling / Floor | Used when a specific, directional rule for handling fractions is non-negotiable (e.g., for certain scores, safety margins, or inventory management where partial units are unusable). |

This matrix serves as a guide, but remember that edge cases and unique requirements will always necessitate careful thought. The ultimate responsibility lies with the algorithm designer to understand the implications of each choice.

Reinforcing the idea that understanding these mathematical functions is key to robust algorithm design in any programming language, this knowledge empowers developers to craft reliable, accurate, and contextually appropriate solutions. As we move forward, we’ll summarize these crucial techniques and their broader impact.

Frequently Asked Questions About From Decimal to Whole: 3 Easy Methods You Should Know Now!

What does it mean to convert a decimal to a whole number?

Converting a decimal to a whole number means finding the nearest whole number value. There are a few different methods you can use to achieve this, depending on the context and desired level of accuracy.

Why would I need to know how to get a decimal to a whole number?

Knowing how to get a decimal to a whole number is useful in many real-world scenarios. For example, when estimating costs, calculating quantities, or simplifying measurements.

What are the common methods to transform decimals to whole numbers?

Common methods include rounding, truncation (or flooring), and ceiling. Rounding considers the decimal value, while truncation simply removes it. Ceiling always rounds up to the next whole number.

When is it appropriate to use different methods to learn how to get a decimal to a whole number?

Use rounding when you want the closest whole number. Use truncation when you want to discard the decimal portion entirely. Use ceiling when you always want to round up to the next highest whole number.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ve navigated the intricate world of converting decimal numbers to whole numbers, exploring three distinct yet equally vital methods: Rounding, Truncation, and the versatile Ceiling/Floor functions. We’ve seen that each method has its unique characteristics, making it suitable for particular contexts – from maintaining financial accuracy with specific rounding rules to ensuring minimum allocations with ceiling functions, or simply extracting the integer part with truncation.

The fundamental takeaway is clear: there is no universally superior algorithm. Instead, the best algorithm is always dictated by your specific scenario and the project’s precise requirements for precision, accuracy, and error handling. By truly understanding these mathematical functions and their implications, you are now equipped to make informed decisions that will significantly enhance the robustness and reliability of your data processing. So, go forth and confidently apply these essential skills, ensuring robust and reliable data type conversion across all your programming languages!